Sculpting time! I was super excited to start making for this project.

In preparation for sculpting Edith Kramer, I wanted to build an impression of her by watching any online documentaries and talks she was a part of, and reading her work. My perception of Edith is a soft-tempered woman with a lot of experience, and a strong personal and emotional understanding. She also has a quirky attitude towards her, which is particularly displayed in this documentary video.

In terms of reference images, I used digital photographs and screen grabs from videos. I scaled them to be the same size and printed out to take measurements from. I ensured these were all from different viewpoints, in order to create an environment as similar to sculpting from a life model as possible. This would aid the three-dimensionality of my sculpt.

An impactful issue I encountered at this point, was the quality of the images. This became far more important in the tertiary details stage of sculpting, when I was looking at wrinkles and skin texture. As I couldn’t see this on the images, I also used stock images of elderly individuals to compare and analyse the way skin presents itself at that age, and to also refer to anatomy features which were covered by clothing, such as the neck and back.

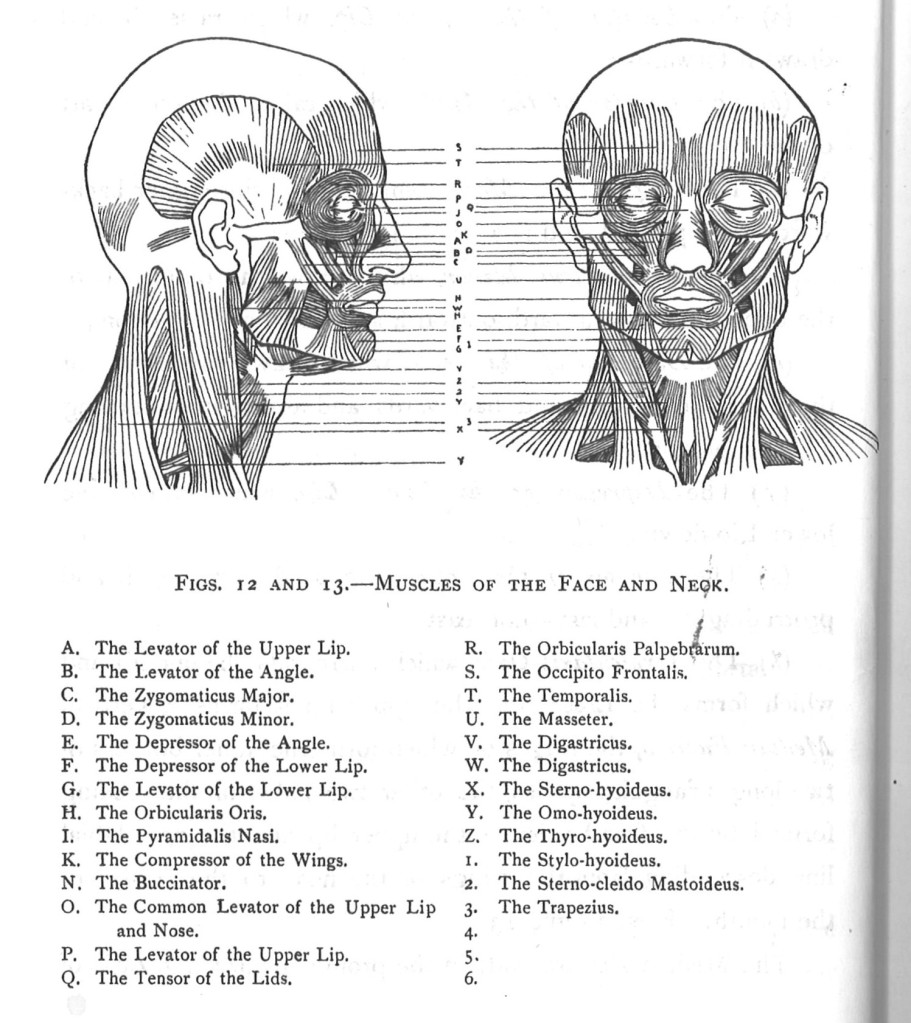

An understanding of anatomy was significant to my sculpt. Consequently, I did not only use images of different features of the face and body to, I also worked quite closely with Edouard Lanteri‘s book Modelling and Sculpting the Human Figure (1965). He was a French sculptor and teacher at the Kensigton School of Art, who was quite influential to the New Sculpture movement through his Romantic style of sculpting. His book presents a thorough understanding of human anatomy, while guiding the reader through step-by-step process of building a human bust from underlying bones, muscles, tendons and fatty tissue base.

‘The book is a gold mine of technical information, the kind of reference work that should be a lifelong studio companion to the figure sculptor.’

Hale, N. C. (1965) pg. vi in Introduction to Modelling and Sculpting the Human Figure

One of the numerous tips I have gained from his teachings is the way that understanding the anatomy can help a student express the emotionality of the subject, such as in the sense of the lips. In his book he describes the anatomy of the muscles surrounding of and around the lips, and how they work together to make different facial expressions, such as smiling. Getting a more thorough understanding of anatomy helped me to build more narrative into my sculpt, of which importance I have established in an earlier blog post. As such, I sculpted a soft smile with a slight upturn of the corners of the mouth to represent her idiosyncratic characteristics which I have learned from watching numerous interviews and reading her work.

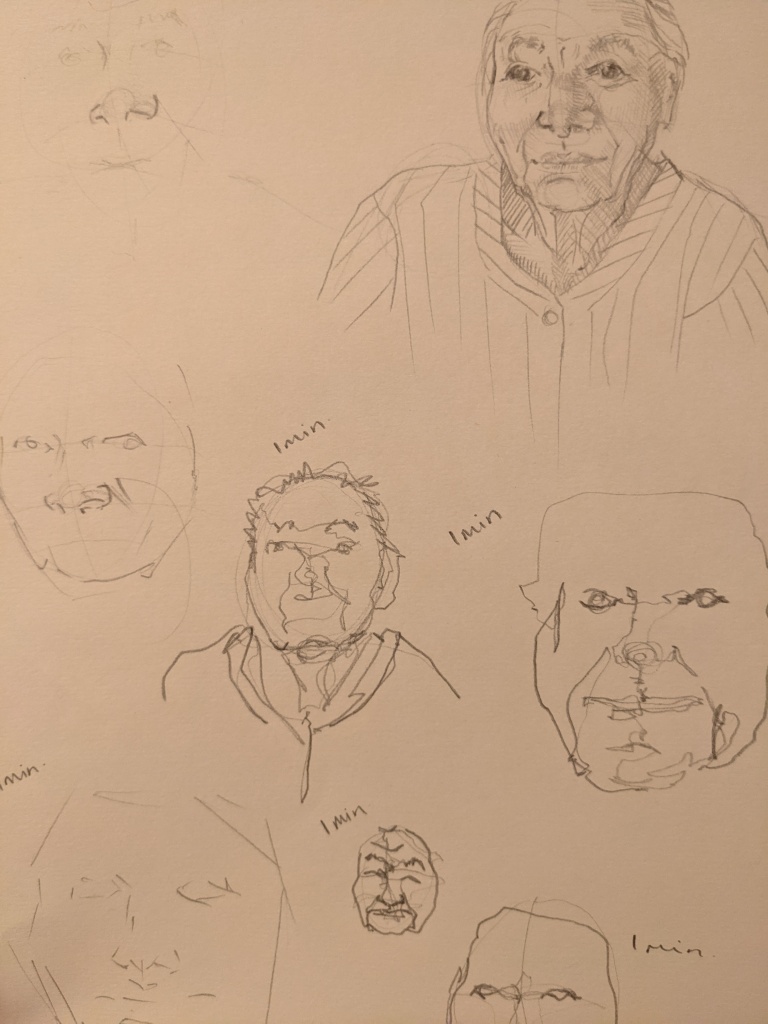

Additionally, the beginning few chapters of Lanteri’s book emphasise practicing before commencing onto a more complicated sculpt, in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional forms. Thus, I began by sketching and painting Edith Kramer, after which I sculpted her facial features individually, before commencing onto a 3-day maquette sculpt. This allowed me to curiously explore both her physical features, and the material which I would portray them with. I believe these tests were fundamental to the final model, as they gave me freedom to practise and make mistakes, which helped me to aim for my benchmarks of quality I established in an earlier post.

Oil painting of Edith Kramer.

Quick sketches of Edith Kramer.

Longer sketches of Edith Kramer in different materials.

Quick clay study of the mouth.

A second nose, a quicker study.

Clay ear exploring forms.

Clay nose with skin texture.

3-day maquette sculpt to explore the process of portrait sculpting.

The final sculpt, I chose to do in Plaxtin. While clay is traditionally used by the Madame Tussaud’s workshop, Plaxtin is wax based which means I did not have to keep it constantly dry, while still retaining the consistency of clay. There were some disadvantages to using Plaxtin instead of clay however – as the material didn’t dry out and harden over time, it stayed its base consistency of softness all the way through sculpting. Due to this, it was harder to sculpt in small details in the final stages, but I managed this by using cling film and a steady hand.

While Lanteri’s book was super helpful, I still struggled with getting the right anatomy in my sculpt though, particularly around the mouth and nose areas, and finally the ears. No matter what I did, and which references I looked at for help, there was something really wrong that I could not figure out. I got in touch with Val Adamson who runs a sculpting studio. I don’t think I would have ever noticed the things she pointed out! For instance, the issue with the mouth and nose area, was so obvious after she changed my perspective – I started the upper lip skin from the back of the nostrils, rather than the middle. Use the slider below to see the before and after differences.

I believe making contact with a more experienced sculptor, was crucial to the final quality of my sculpt, as it influenced the way I approached my making process. This was a link to Edith Kramer’s teachings – a creative environment helped me to understand the restrictions of my perspective and how it is important to reach out. I think this understanding behind the making not only improved its realism and quality, but also encouraged me to deal with struggles and problem-solving in an approach based on curiosity.

Lastly, earlier in the project I predicted some problems that may have occurred at this stage (click here to read this post!). Let’s address these now:

- The armature was just the right size due to my experimentation with some quick sculpts before starting the final.

- The eyes are the right depth. Prioritising measurements throughout was crucial.

- By constantly referring to anatomy images, the teachings of Edouard Lanteri, and the advice of the wonderful Val Adamson, I was able to fix my mistakes. As I am an amateur at this, I would not have reached this quality without reaching out to others. Therefore, the facial features looked cohesive.

- This did occur once – I finished the details on the area joining the nose and the mouth while this area was still anatomically wrong. I fixed the anatomy after contacting Val, however this meant I had to redo the details.

Overall, I had a lot of fun and frustration during this stage of the project. Most notably, I am glad I prepared by completing theoretical research behind all the materials I would use throughout the project, and the purpose, narrative and benchmarks of the model. It ensured a holistic understanding of the process, adding meaning to my making.